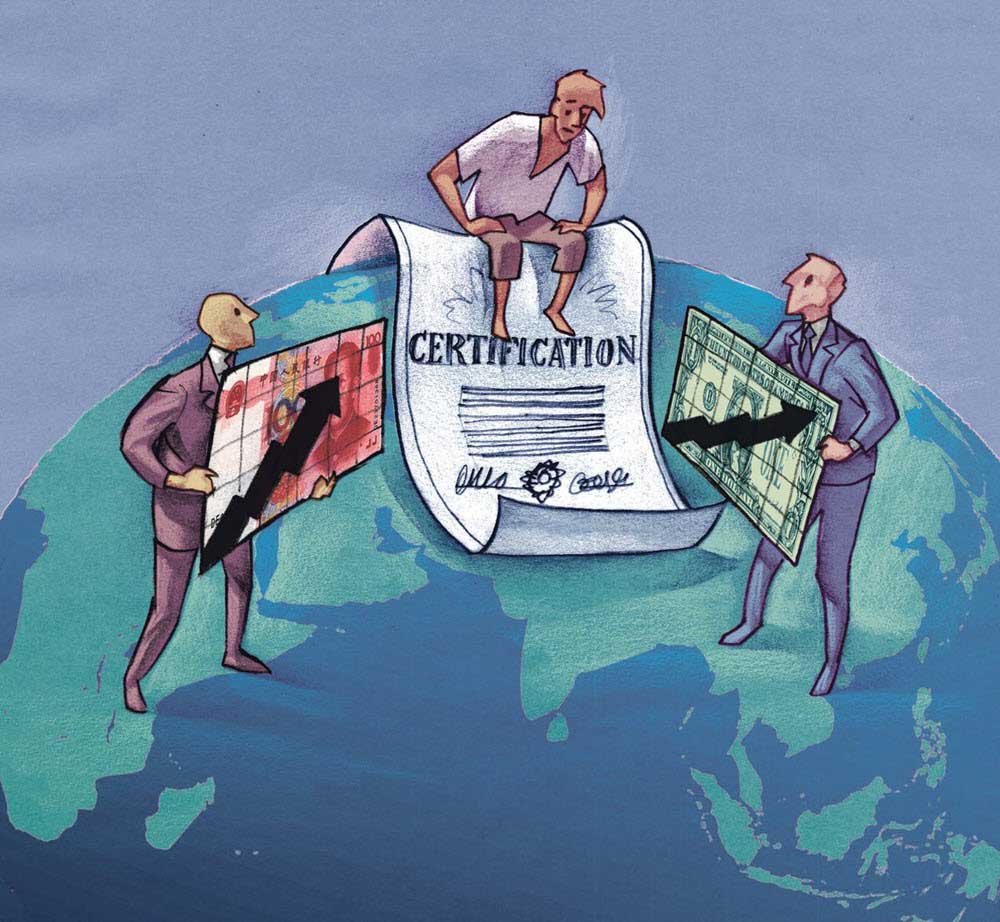

A plan to unleash the power of ownership by formalizing capital in the informal economy.

By Hernando de Soto

Originally published in the Wall Street Journal

Aug. 11, 2020 1:42 pm ET

A proxy for the contest between American and Chinese capitalism will take place in developing countries, where institutions are manifestly not coping with the economic recession triggered by Covid-19. The two billion people who work outside the global financial system in the informal economy suffered a 60% drop in income in the first month of the crisis, according to an April press release from the United Nations’ International Labor Organization. Guy Ryder, the agency’s director-general, said: “Millions of businesses around the world are barely breathing. They have no savings or access to credit.” Without help, “these enterprises will simply perish.”

Unlike China, the U.S. and other developed nations, these countries do not have capital and credit-creating institutions that can continually generate funds. To finance a virusinduced recession, developing countries can rely only on their monetary savings and capacity for debt, which will quickly be depleted. Both Thomas Jefferson and Karl Marx called this financing “fictitious capital” money backed by nothing more than a government’s ability to tax its citizens. Real capital has to be based “on those who have property,” as Jefferson put it.

In the contest between Chinese and American models of capitalism, developing countries will side with whoever offers them not more debt but the opportunity to create capital based on property. And though almost no one realizes it, the people in the informal economy now have titles to most of the surface of the earth, as a result of decades of squatting, migrations, agrarian reforms and skirmishes. These people control access to most of the mineral, oil and gas reserves in the world. But they often feel exploited by industry and use their titles to block access to $150 trillion of proven reserves, five times the combined gross domestic product of the U.S. and China.

Instead of blocking projects, why don’t those with property use their titles to create capital by pledging them against investment or credit to fund their own mines or businesses, or as credentials that would allow them to negotiate with oil and gas firms on equal terms?

Because their titles need a chain of certifications issued by escrow and closings organizations, trust services, title and fidelity insurance firms, originators, underwriters, securitizers and other agencies. This process is so ingrained in American society that it is taken for granted, and the purpose is all but forgotten. Link by link, these certifications reinforce and expand the rights contained in local titles to do two things: include safeguards that financial markets require to prevent fraud; and allow titleholders to own not only the value of resources in their passive state but also the added value of the enterprises that develop them, which can be circulated through an economy in the form of stock.

Once this value chain of certifications is packaged in a file by a fund originator, that title will be acceptable at the reception window of a bank as a pledge and credited in its accounting books as an asset, and, voila! it is capital. The bank can then issue money through an exit window, recording it in its books as a debt, and that money can be invested to create surplus value.

The reason those in the informal economy are at risk of perishing in this pandemic is a monstrous myth: that property-rights documents begin and end with simply obtaining a title. The truth is that if those property documents are not enriched by the additional certifications, the surplus value that ownership is supposed to produce cannot be realized.

The challenge is to explain this process to those who hold the titles. What worked for me in Peru was pointing people to the waters of Lake JunIn, high in the Andes, which generate much of the power for Peruvian industry. I explained that capital, like energy, is the abstract potential that all resources have. For this potential to be realized, it has to be transformed through a chain of documents: those certifying the potential energy of the water by measuring its volume and elevation, those certifying the amount of kinetic energy it could generate at the end of its gravitational fall, and those certifying the turbines and generators needed to turn kinetic energy into controllable electricity that, when it reaches households and businesses, is worth thousands of times the recreational value of the placid lake.

I then explain that the invisible chain needed for capital creation is in place in nearly all developing countries—enshrined during the past 30 years in international conventions, free-trade and bilateral investment agreements, and domestic legislation. As a result of working with heads of state in some 20 countries, I have helped create a path that connects all the links in the chain and then designed and tested a protocol that would allow a credible agency to supply the certifications owners can add to their titles.

When Covid-19 hit Peru’s economy in early May, I proposed a plan to implement the chain of certifications to the titles of local landowners blocking the extraction of mineral reserves with proven potential value of $1 trillion. These certifications could be issued by some of the American, Swiss or Chinese banking and title-insurance institutions with which I have spoken with over the past two years.

Peru’s seven mining federations, representing 400,000 families, support my plan and have publicly challenged the president to promote it. I posted summaries of the plan on social media and got nearly seven million views on my Facebook page within two days.

Those in the informal economy are willing to embrace capitalism. Whether it will be China’s or America’s model will depend on which country understands that while no one was looking, the poor inherited the surface of the Earth, and that they will favor whoever helps them use their legacy to create capital rather than destroy it.

Mr. de Soto is author of “The Mystery of Capital” and a former CEO of UEC, Switzerland’s largest consulting engineering firm.